Traditional Managerial Accounting

This page describes the history of accounting and the most well-known traditional managerial accounting methods.

History of Accounting

Information on commercial transactions has existed for as long as

people have traded with one another. Ancient civilizations engraved bookkeeping records

on stone tablets. More than five hundred years ago, Luca Pacioli, a mathematician monk,

described the basics for a double-entry booking system. With this double-entry system traders

could determine the results of the transactions they made in the market and could also determine

their assets and debts.

During the industrial revolution a lot of production was transfered from individuals

to large companies (texile mills, steel factories, etc.). The whole production and selling

of products consisted of several conversion processes which were all performed in these

large companies. Conversion processes that formerly were supplied at a price through

market exchanges became performed within one organization. A lot of internal transactions

occurred as conversion processes supplied their output to a next process within the organization

instead of selling their output on the market. Owners of these large companies devised systems to

summarize the efficiency by which labor and material were converted to finished

products. These early managerial accounting systems produced efficiency measures such as cost per hour or

cost per pound produced per process and per worker. These measures were used to motivate and

evaluate the workers and their managers (Johnson and Kaplan, 1987, pp 6-12).

Early Cost Accounting Systems

In order to calculate the costs of a product, the direct labor costs and direct material costs ('prime costs')

of a product were summarized. At the end of the nineteenth century companies also included indirect costs

("overhead") when calculating the costs of a product. According to Church and Mann, most companies determined

the indirect costs of a product as a percentage of the direct labor costs (Solomons, 1952, pp 22-23). In 1910

Church wrote "it is a very usual practice to average this large class of expense (red. indirect costs),

and to express its incidence by a simple percentage either upon wages or upon time. That this plan is entirely

misleading there can be very little doubt, because few of the expenses in the profit and loss accont

have any relation either to each other or to wages or to time. To rely upon an arbitrary established percentage ..

is valueless and even dangerous" (Church, 1910 pp 79-81).

When determining the costs of a product, Church advocated dividing the factory into a series of 'production centers'

(e.g. a machine and a group of workers). In this production center method, the costs of each production center

are summarised. The hourly rate of each production center expresses the total costs of the production center per

hour. The costs of a production center is then loaded on to the work passing through it, at an hourly rate.

(Solomons, 1952, pp 25-27).

Early Budgetary Control Systems

Budgeting as a tool to forecast expenses is an old practice. Joseph in Egypt made a budget of corn supplies and

planned Pharao's investment and consumption policy in the light of it. In Great Britain the practice of drawing

up a government budget each year is about 250 years old. In 1911 Bunnell described that each item of overheads

was to be budgeted and compared with the actual expenditure under each head as a way to control costs. This budget

for each item of overheads was a fixed budget, which was not adjusted for changes in the number of products produced.

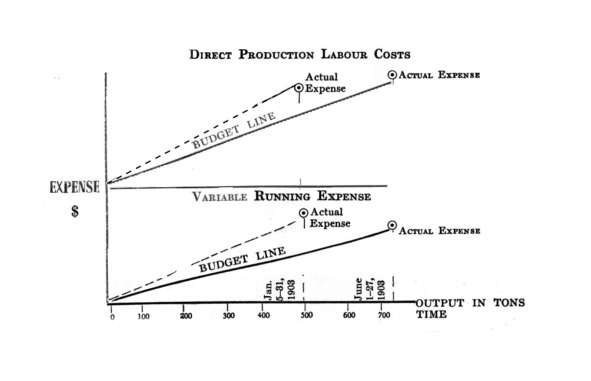

In 1903 Henry Hess described the basic idea of what we now call a flexible budget. Hess used a graphical method

to compare the budgeted expenditure and actual expenditure. For each main group of expenses (for instance direct

production labor costs) he plotted a straight line, representing the relationship between expenses and output.

Thus the budgeted expenses were adjusted for changes in levels of output (Solomons, 1952, pp 45-49).

Scientific Management

At the Springfield Armory in Massachusetts, Tyler developed performance standards for employees, which were

determined scientificly. Already in 1842 Springfield Armory implemented Tyler's system and recorded the peformance,

and deviations from the performance standards per employee (Ezzamel, Hoskin and Macve, 1990, pp 159-160). Several

years later, the US Railroads, used the 'operating ratio' (revenues / costs) to measure the performance of managers

(Hoskin and Macve, 1988, pp 39-50). At the end of the nineteenth century, several engineers in metal working firms,

developed standards for the use of materials and labor in manufactoring tasks. They used scientific

methods (such as time-and-motion studies) to determine these performance standards. One of these 'Scientific Management'

engineers, Taylor, created a system which compared the actual use of labor and material with the performance standards

in order to monitor physical labor and material effiencies (Johnson and Kaplan, 1987, pp 48-51). According to Ezzamel,

Hoskin and Macve, 'The Springfield workers were the first to become accountable under the new system; then in the

railroads it were managers who became accountable' (1990, p 161). And according to Miller and O'Leary, 'Tyler's

achievement was to invent Taylorism avant le mot' (1987, p. 287).

Managerial Accounting Standard Costs and Variances

At the beginning of the twentieth century companies started to use performance standards to determine the

standard costs for processes and products (Solomons, 1952, pp 38-49). The standard costs of a product or a

process are predetermined measures of what costs should be. The standard costs of a product for instance are

determined by multiplying the standard use of labor, materials, machines, etc. per product by the standard price

of labor, materials, machines etc. These standard costs might be compared with the actual costs in order to monitor

the efficiency in companies. The difference between standard costs and actual costs are analysed in a

variance analysis. Already in 1920, G. Charter Harrison wrote a set of formulas for the analysis of these cost variances.

(Solomons, 1952, pp 50). Today companies still compare their predetermined or budgeted costs with their actual costs in

a variance analysis. In a complete variance analysis companies also compare their budgeted sales with actual sales.

A simple example of a variance analyis is given below:

| budgeted sales volume * budgeted selling price: | 1,000 products * 50.00 | = | 50,000 |

| actual sales volume was lower: only 900 products: | 900 products * 50.00 | ||

| - ------------------------------ | |||

| sales volume variance: | - 100 products * 50.00 | = - | 5,000 |

| . | |||

| the actual selling price of the product was also lower: | |||

| 48.00 instead of 50.00: variance = - 2.00 lower | |||

| selling price variance: | 900 products * - 2.00 | = - | 1,800 |

| . | |||

| the standard use of labor per product is 1.0 hour and | |||

| the standard price of labor is 40.00 | |||

| in this simple example no other costs are involved | |||

| the total standard costs allowed (flexible budget): | 900 products * 1.0 * 40.00 | = - | 36,000 |

| the actual use of labor per product was only 0.9 hour: | 900 products * 0.9 * 40.00 | ||

| - ------------------------------ | |||

| efficiency variance | 900 products * 0.1 * 40.00 | = | 3,600 |

| . | |||

| the actual price of labor however was higher: | |||

| 41.00 instead of 40.00 = 1.00 higher | |||

| labor price variance: | 900 products * 0.9 * - 1.00 | = - | 810 |

| + | ---------- | ||

| actual result: | | 9.990 |

Return on Investment

Around 1900, many mass producers, acquired there own distribution channels and own

sources of raw materials and other inputs. These firms performed several activities

which were formerly performed by individual companies. Manufacturing, purchasing,

transportation and distribution became integrated in these multi-activity firms. In

these vertically integrated firms, many individual departments still relied on their

own measures of efficiency. Most of these efficiency measures however could not be

related to overall company profit. In order to monitor the contribution of each activity to

overall profit they developped a new performance measure: return on investment.

The return on investment (income / invested capital) ratio helped top management to monitor

the profitability of each individual activity (Johnson and Kaplan, 1987, pp 61-93).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Church, A. H.,'Organisation by Production Factors', Engineering Magazine, April 1910.

- Ezzamel, M., K. Hoskin and R. Macve, 'Managing It All By Numbers: A Review of Johnson & Kaplan's 'Relevance Lost', Accounting and Business Research, vol. 20, 1990, pp 153-166.

- Hoskin, K. W., and R. H. Macve, 'The Genesis of Accountability: The West Point Connections', Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1988, pp 37-73.

- Johnson, H. T. and R. S. Kaplan, 'Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting', Harvard Business School Press, 1987.

- Jorissen, A., 'Management accounting: een revolutie op de drempel van de 21ste eeuw?', Economisch en Sociaal Tijdschrift, december 1993, pp 551-590.

- Miller, P. and T. O'Leary, 'Accounting and the Construction of the Governable Person', Accounting, Organizations and Society, 1987, pp 235-265.

- Solomons, D., 'Historical Development of Costing', Studies in Costing, Sweet & Maxwell, 1952, pp. 1-51.